- What would you include in a blood test for a patient with a venous ulcer?

- What alterations would you expect to find, whose adjustment may have a direct impact on wound healing?

This post aims to provide guidance on these questions, the answers to which, at present, are not agreed upon. Let’s see what the published studies say about this!

The idea of writing a post on this topic came to me when I read the article published last month “Nutrition status in patients with wounds: a cross-sectional analysis of 50 patients with chronic leg ulcers or acute wounds”. Among the authors of the study, in addition to dermatologists and internists, we find a psychologist, an essential specialist, as we will see, to address the nutritional problems of people with leg ulcers.

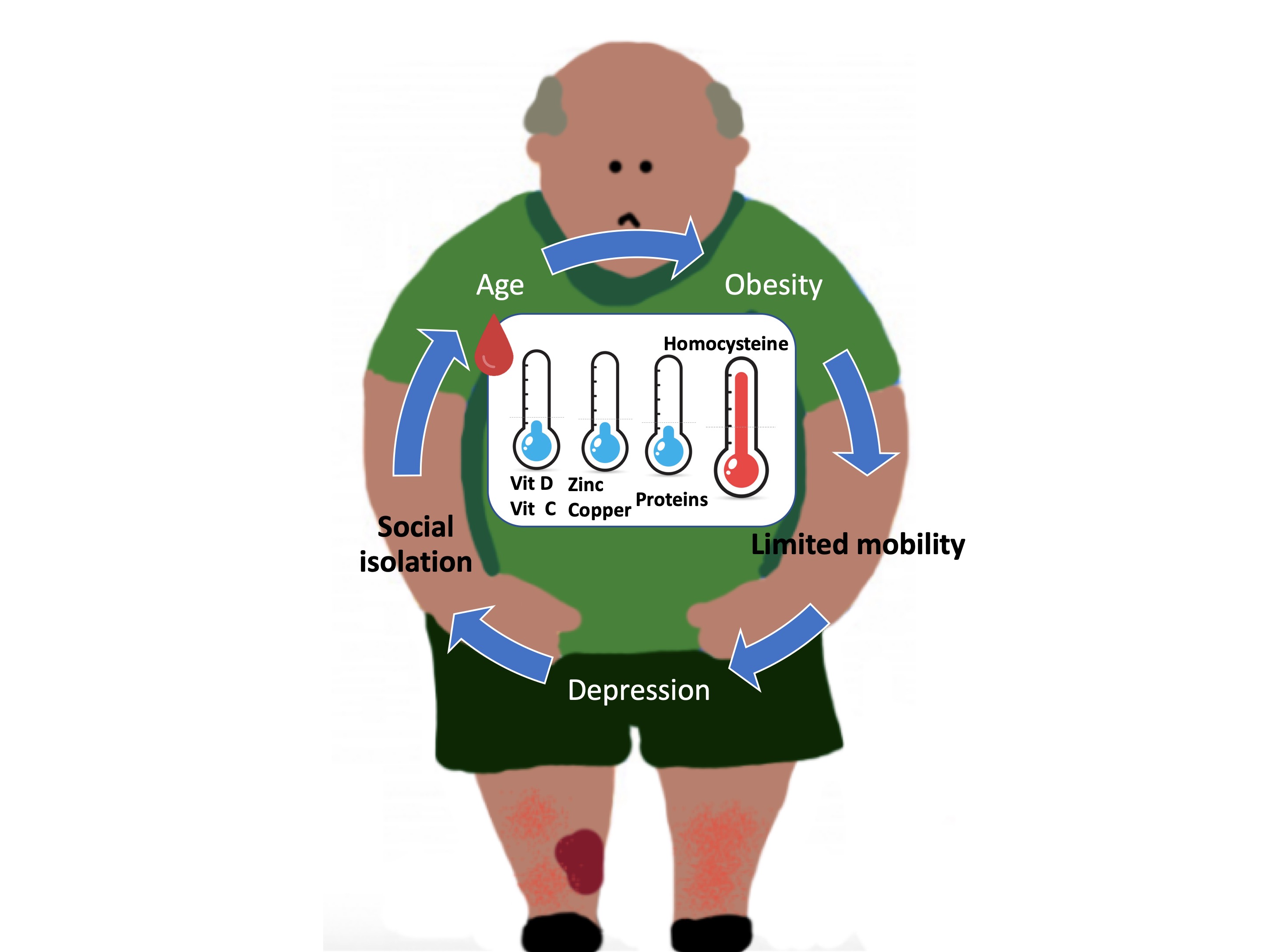

When we talk about nutrition and wounds, the first thing we always think about, and in fact this is what has been mostly studied, is the relationship between nutritional deficit and poor evolution of pressure ulcers. However, this idea of a nutritional approach should be integrated into the therapeutic strategy of any wound, especially in elderly patients. In fact, age, with the associated decrease in taste and appetite, as well as problems with chewing, is a major risk factor for malnutrition. Malnutrition results not only from low calorie intake, but also from a lack of micronutrients. In other words, obesity, which is so common in our patients with leg wounds, can be accompanied by a nutritional deficit due to a diet poor in vitamins and essential amino acids. Patients who live alone, suffer from depression or have little mobility for shopping and preparing food are also at risk of malnutrition.

Interestingly, there is an overlap of risk factors for malnutrition and venous ulcers: age, obesity, social isolation, depression, poor mobility. And it is in a vicious circle, so a psychosocial approach is essential for the holistic treatment of these patients.1

Well, coming back to our patient with a venous leg ulcer, what alterations should I look for in his blood test to treat them and improve wound healing?

I can tell you that, at this moment, there is no consensus on what nutritional parameters to ask for, nor if, in the event of finding alterations in their levels, dietary supplements have an impact on wound healing… But let’s see what has been studied about this… First of all, I would like to stress that no association has been found between malnutrition and the size or duration of the leg ulcer.1,2

VITAMINS

- VITAMIN C

Its deficit is frequent in patients with leg ulcers. This vitamin is fundamental in the inflammatory phase, since it is involved in the apoptosis of neutrophils, and in the proliferative phase, since it participates in the synthesis of collagen. Clinical trials are needed to detect the usefulness of its supplementation in leg wound healing.1,2

- VITAMIN D

Its deficit is frequent in the general population. In fact, in studies with a control group, such as the one we indicated at the beginning of the post, this deficit is found in both groups, even though it is more frequent in the group with leg ulcers. This may be due to the reduced mobility of these patients, with less exposure to sunlight. The anti-inflammatory effect of the vitamin may be of interest in modifying the pro-inflammatory environment of chronic ulcers. A clinical trial compared supplementation with 50,000 IU per week of vitamin D for 2 months with placebo in patients with venous ulcers and a deficit of vitamin D. Despite finding a trend towards greater healing rates in the treatment group, the differences are not significant, the number of patients included is small and the variability of lesion sizes is very high .

TRACE ELEMENTS

- ZINC

This trace element was the main character of a previous post (“Why do we use topical zinc on wounds and perilesional skin?”)… In fact, in its topical presentation it is one of the main treatments used in our clinic... However, while its topical use is widespread, the available evidence does not support the interest in healing of oral zinc administration, even if there is a deficit of it.1 It must be taken into account that clinical trials are scarce, of small size and multiple limitations, as highlighted in the conclusions of the last Cochrane review on this subject.4

PROTEINS

While protein supplements are a well-established strategy in pressure ulcers, in venous ulcers this recommendation does not exist, even though many of these patients have hypoproteinaemia. The most common measure for testing blood protein levels is serum albumin concentration. This protein deficit is thought to be associated with the catabolic state of having an ulcer, due to increased metabolic demand, rather than protein loss in the exudate.1,5

However, there is one amino acid that is frequently elevated in patients with leg ulcers:

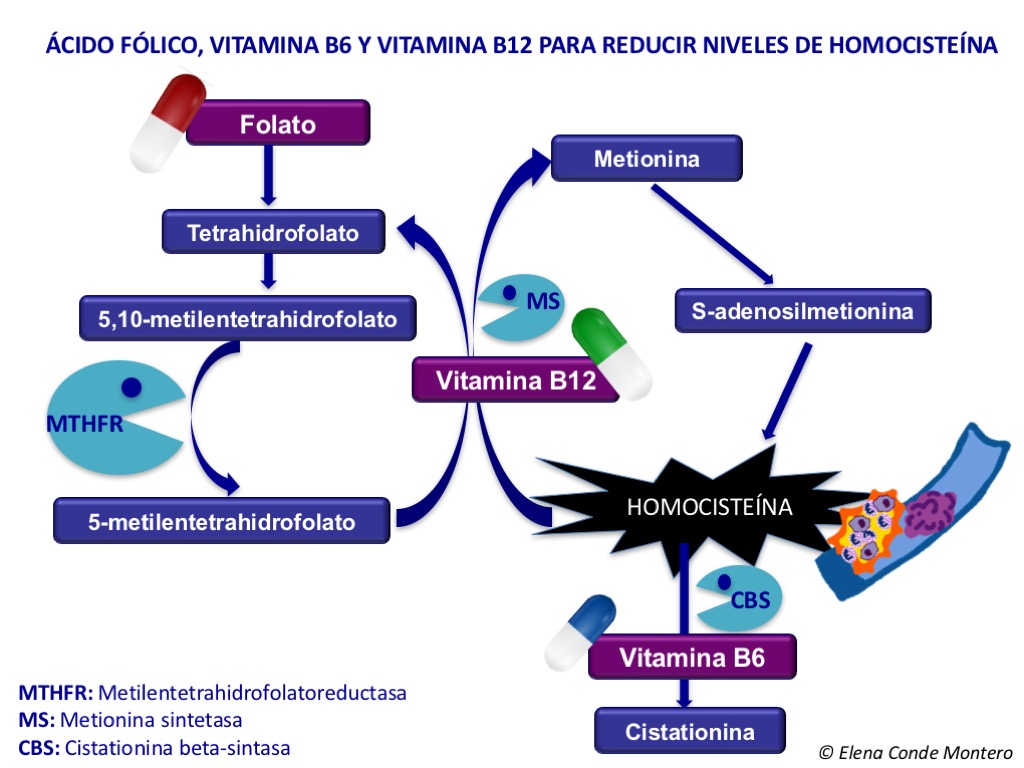

- HOMOCYSTEINE

Homocysteine is a sulfur-derived amino acid derived from methionine, in whose metabolism several enzymes are involved. It has a cytotoxic action on the endothelium, increasing pro-inflammatory factors and oxidative stress. It also facilitates platelet adhesion, hence its potential thrombogenic effect. Its high levels in blood, hyperhomocysteinemia, is considered an independent risk factor for arterial and venous thrombosis, and is usually related to old age, renal failure, genetic and nutritional factors, in addition to being a marker of tissue damage. Considering this microthrombosis-enhancing action, it is easy to think that homocysteine is involved in the development of venous ulcer, but it should not be forgotten that it can also simply be a marker of tissue damage…6

Studies comparing blood homocysteine levels in patients with chronic venous insufficiency, with and without ulcers, with a control group always detect a higher concentration in patients in the first group, with statistically significant difference. Furthermore, there seems to be no correlation between the evolutionary stage of chronic venous insufficiency and hyperhomocysteinaemia. A study that included arterial, venous and mixed leg injuries also found no association of hyperhomocysteinemia with any of these particular etiologies.6

As we discussed in the post “Ulcer secondary to alteration of homocysteine metabolism mimicking pyoderma gangrenosum”, the treatment of hyperhomocysteinemia is very simple, since the contribution of folic acid facilitates the conversion of homocysteine into methionine. This scheme on homocysteine methionine metabolism also helps us understand why vitamin B6 and B12 would be interesting as well.

So, is there a causal relationship between leg ulcer and hyperhomocysteinemia? Is hyperhomocysteinemia a cause or a consequence? Does lowering the homocysteine concentration have an impact on leg wound healing?

Although different studies have been conducted to analyse the prevalence of hyperhomocysteinemia in patients with leg ulcers, none has been designed with the aim of studying its potential causal relationship. Therefore, we know that hyperhomocysteinemia is common in leg ulcer patients but we do not know exactly why.6

Regarding the benefit of treating hyperhomocysteinemia on wound healing, more studies are needed. What does seem clear is that reducing hyperhomocysteinemia does not reduce cardiovascular and thromboembolic risk.6 One clinical trial examining the value of daily folic acid supplementation for 1 year in patients with leg ulcers and hyperhomocysteinemia found statistically significant differences in the healing rate in favor of the treated group. It is a safe and simple treatment, so although there is not much evidence and at the moment we do not know if the elevated homocysteine is a cause or a consequence, I think it is interesting to start the treatment.

As we have just seen, the available evidence doesn’t make it clear at all which deficits have a direct impact on healing and which nutritional supplements are useful in people with leg ulcers. In fact, it would be also interesting to conduct studies in order to determine whether these nutritional supplements are interesting in patients with normal serum values… The benefit of these supplements might be only achieved at higher doses than those considered normal… What an unresolved dilemma! What is clear is that we have to recommend (besides explaining) is a healthy diet.

My friend Nicolas Kluger, dermatologist and artist, explains it to us with a watercolor 🙂 Je te remercie pour ta belle peinture, Nicolas!

I would like to finish with a “NUTRIPSICOSOCIAL” reflection: Considering that obesity, lack of mobility and depression are modifiable risk factors for malnutrition (age unfortunately is not), let us try to modify them to improve the nutritional status of people with leg ulcers!

References:

- Renner R, Garibaldi MDS, Benson S, Ronicke M, Erfurt-Berge C. Nutrition status in patients with wounds: a cross-sectional analysis of 50 patients with chronic leg ulcers or acute wounds. Eur J Dermatol. 2019 Dec 1;29(6):619-626.

- Barber GA, Weller CD, Gibson SJ. Effects and associations of nutrition in patients with venous leg ulcers: A systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:774– 787.

- Burkiewicz, C. J. C. C., Guadagnin, F. A., Skare, T. L., Do Nascimento, M. M., Servin, S. C. N., & de Souza, G. D. (2012). Vitamin D and skin repair: A prospective, double-blind and placebo controlled study in the healing of leg ulcers. Revista do Colegio.

- Wilkinson Ewan, A. J. Oral zinc for arterial and venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012.

- Legendre, C., Debure, C., Meaume, S., Lok, C., Golmard, J. L., & Senet, P. (2008). Impact of protein deficiency on venous ulcer healing. Journal Of Vascular Surgery, 48, 688–693.

- Studer M, Barbaud A, Truchetet F, N’guyen PL, Bursztejn AC, Schmutz JL.[Hyperhomocysteinemia and leg ulcers: A prospective study of 68 patients]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011 Oct; 138(10):645-51.

- de Franciscis, S., de Sarro, G., Longo, P., Buffone, G., Molinari, V., Stillitano, D. M.,Serra, R. Hyperhomocysteinaemia and chronic venous ulcers. International Wound Journal. 2015;12: 22–26.

Also available in: Español (Spanish)