Unna boot is not something new. In fact, it’s something very old (almost as old as punch grafting:). I was waiting for the slightest excuse to write about this type of bandage and take the opportunity to comment on the versatility of the use of zinc oxide impregnated bandages… The truth is that scientific publications on this subject are not frequent, so, as an article on the history of this bandage1 and a literature review protocol2 have just been published, I already have a “current” excuse. If we add to this that our team has talked about zinc impregnated bandages as a therapeutic pearl in several communications and posters of the congress of the Sociedad Española de Heridas (SEHER) that, one more year, has just taken place in Madrid; it is mandatory to talk about zinc oxide again in this blog!

What is exactly the Unna boot bandage?

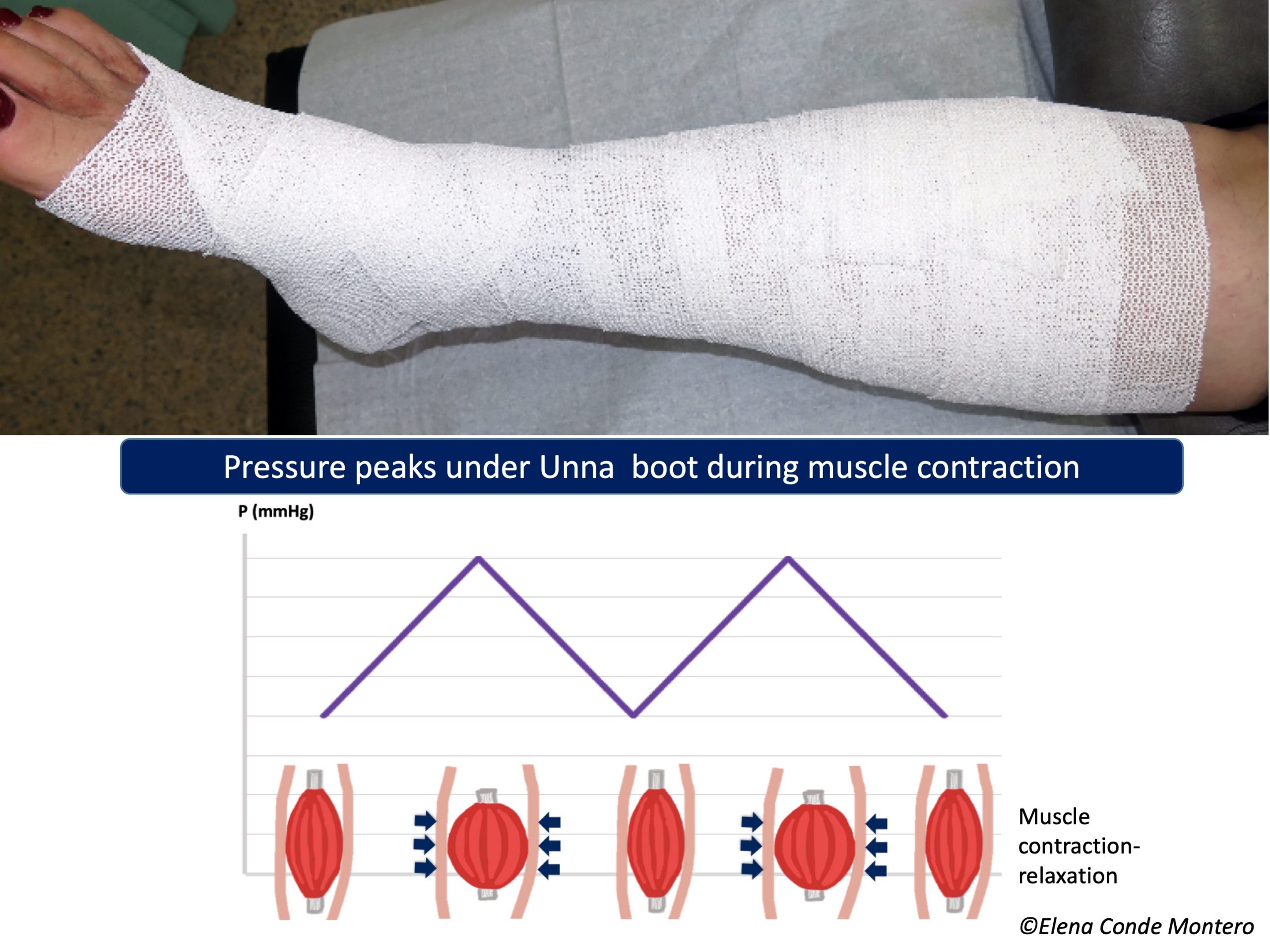

It is a compression system made up of inelastic gauze bandages impregnated with zinc oxide. Therefore, it is a bandage with a high stiffness index, which exerts pressure peaks during the calf muscular contraction, with the consequent reduction of ambulatory venous hypertension (See post “Band and bandage: not the same thing”). In other words, it is an interesting alternative for the treatment of venous ulcers in active patients. The pressure exerted will vary depending on the number and overlapping layers of bandage, as well as the type of secondary bandage applied over it.

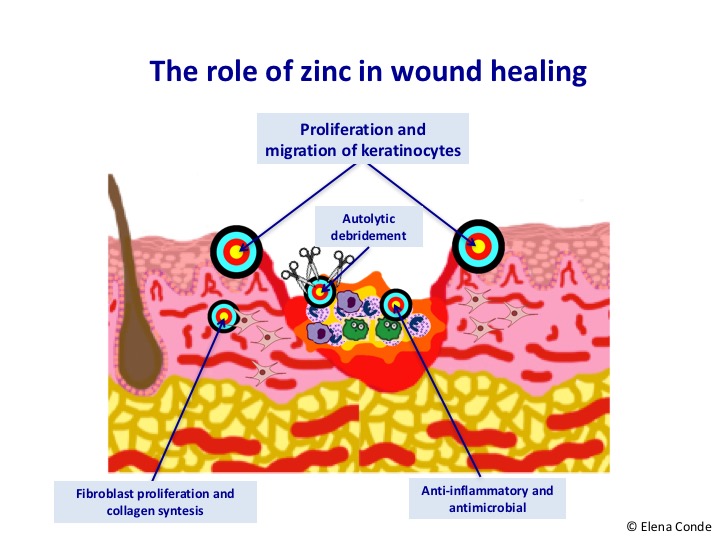

But the benefit of this bandage is not limited to its stiffness, but the fact that it is impregnated with zinc oxide makes it especially interesting. As we commented in the post “Why do we use topical zinc on wounds and perilesional skin?”, zinc oxide has anti-inflammatory and epithelialization promoting properties, very useful in cases of stasis eczema. Different models of this type of bandage have been commercialized, with variability in the concentration of zinc oxide and other moisturizing components, such as glycerin. It is a wet bandage, which dries and hardens on the patient’s skin, without limiting ankle joint movement.

Why is it called Unna boot?

Because it was invented by the German doctor Paul Gerson Unna (1850-1929). This doctor is a very relevant figure in the history of medicine, especially for his interest and research in skin diseases, such as dermatitis. As an alternative to the poorly tolerated compression bandages of his time, in 1885 he invented a gauze bandage impregnated with a mixture of 15% zinc oxide in a glycerin and gelatin-based paste. This mixture had drying and “cooling” effects, as well as anti-pruritic action due to its continuous and slight pressure on the skin. After numerous tests in the following years, Unna presented a new form of compression bandage at the Third International Congress of Dermatology in London in August 1896 and published it that same year. His bandaging technique later became widely recognized for its effectiveness and simplicity.1

What do the studies say about its usefulness?

The studies say FEW THINGS, because they are few, with few patients and very few have a control group… As I commented at the beginning of the post, a group of Brazilian professionals has designed and published a protocol to make an exhaustive review on the subject.2 It is not surprising that they are experts from Brazil, since most of the articles that we find in the literature are signed by Brazilian authors (it is undoubtedly a widespread technique in this country).

The most recent review on Unna boot, published in 2018, highlights the scarcity and low quality of the studies published (14 papers), mostly cases and case series.3

In this context and despite the fact that the available evidence supports and recommends the use of multi-component compression systems, the Unna boot is an economical and efficient alternative in certain countries and for a certain patient profile, especially those active people who present significant eczema associated with venous ulcers.

Practical questions about the use of the Unna boot

Practical questions about the use of the Unna boot

I’m sure that you’re having a lot of questions about how to use this bandage, so here you will find some practical recommendations:

- The frequency of dressing changes will vary depending on the wound exudate, reduction of edema and tolerance to the progressive dryness of the bandage on the skin, but we could keep it on for a week.

- We will use a secondary bandage, whose purpose may be only to protect/fix or also to add pressure. Depending on the objective we are looking for, we will select the type of bandage. This secondary bandage will help to avoid the rapid fall of the Unna boot after the reduction of the edema.

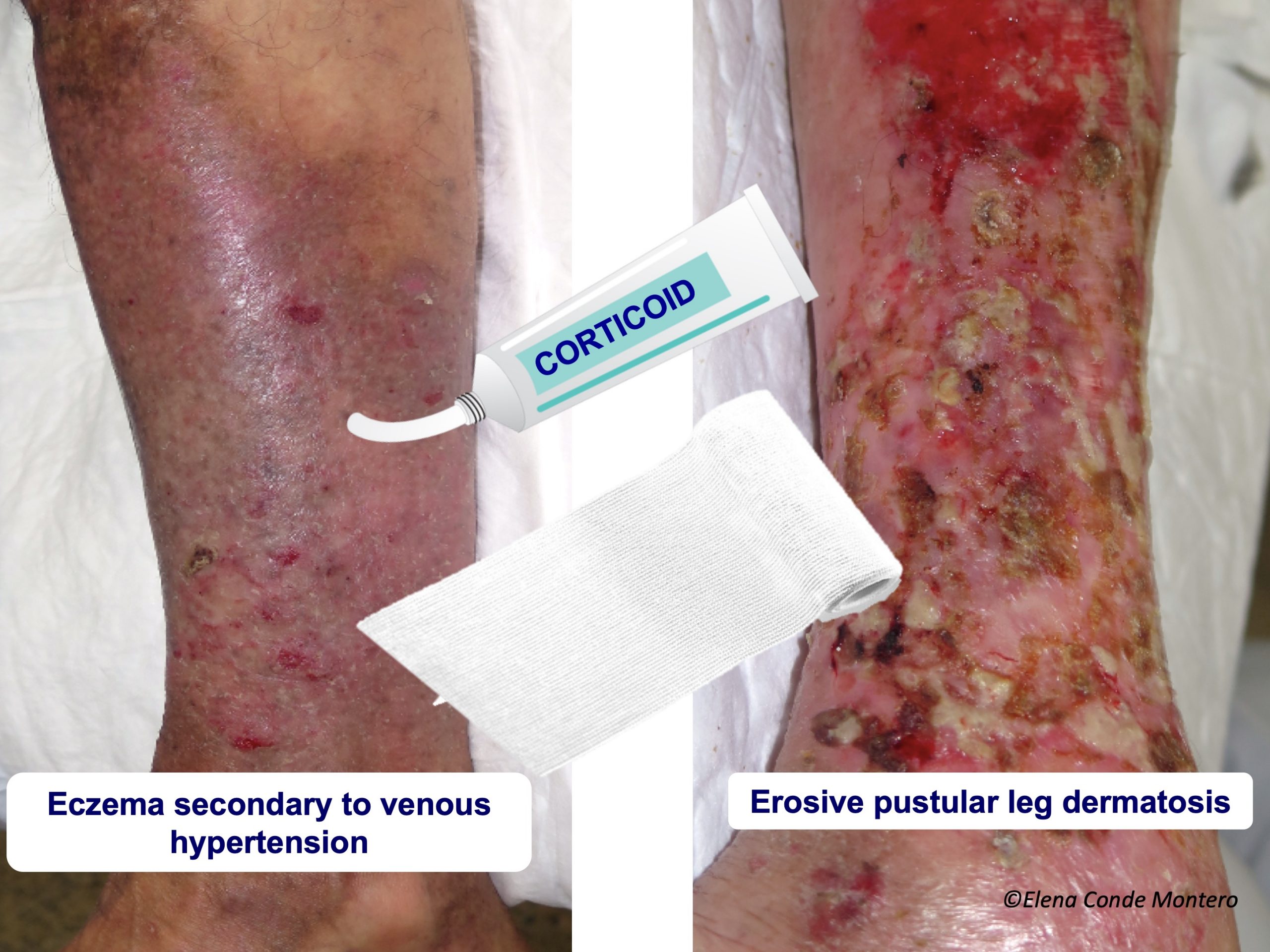

- In cases of eczema, the application of topical corticosteroids prior to the placement of the bandage will reinforce and increase the anti-inflammatory effect.

- The zinc bandage can be the primary dressing for the wound, whose exudate we will control with secondary dressings between the zinc bandage and the secondary bandage.

- It is necessary to avoid folds, because when dry, they will be potential areas of friction and the occurrence of new wounds.

- In older patients with little mobility or thin legs and risk of hyperpressure on bony prominences, associated arteriopathy or lack of sensitivity due to neuropathy, we will not indicate Unna’s boot. In these cases, we will use another type of bandage, for example multi-component bandages, always with protective padding, adapted to the person’s needs.

Beyond Unna boot

Perhaps the “point 6” has discouraged many of you, since this type of patient I describe is very common in the practice… But, as the title of this entry says, zinc-impregnated bandages are not limited to Unna boot! In fact, we often use them as a dressing, primary or secondary, mainly when we have associated eczema (usually in combination with topical corticosteroids). The drying effect of zinc oxide is very useful in case of acute exudative eczema.

To increase the concentration of zinc, we can add zinc oxide in solution or cream. It is a great alternative to protect and treat perilesional skin and very interesting in the wound bed (especially after covering with punch grafting:). During dressing changes,we will avoid cleansing by rubbing to eliminate the residual zinc oxide in the skin since it is not necessary to remove it and, in addition, it would worsen the eczema.

In patients who do not have an active ulcer but do have eczema secondary to venous hypertension, we sometimes recommend that they apply a coricosteroid cream and cover it with a piece of zinc bandage under their compression stocking or self-adjusting Velcro device.

Used as a dressing or bandage, our experience confirms that the zinc impregnated bandage has an important anti-inflammatory action in different leg dermatitis, normally combined with topical corticosteroids, achieving great symptomatic relief. Besides leg eczema, its use in pustulosis and erosive dermatosis is also interesting4 (See post: “: “Pustular and erosive leg dermatosis: you may have seen a case without knowing it “).

“When knowledge that is generated in team is shared in team, the passion with which it is transmitted is exponentially multiplied”. This is what pur team feel whenever we are all at a congress 🙂 Of course, I am also very excited when talking about wounds with my dermatologist friends!

Referencias:

- Tekiner H, Karamanou M. The Unna Boot: A Historical Dressing for Varicose Ulcers. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2019 Dec;27(4):273-274.

- Saidel MGB, Oliveira HC, Dini AP, Kumakura ARSO, Melo Lima MH. Assessment of the use of Unna boot in the treatment of chronic venous leg ulcers in adults:systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2019 Dec 23;9(12):e03209

- Cardoso LV, Godoy JMP, Godoy MFG, Czorny RCN. Compression therapy: Unna boot applied to venous injuries: an integrative review of the literature. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2018 Nov 29;52:e03394.

- Di Altobrando A, Patrizi A, Vara G, Merli Y, Bianchi T. Topical zinc oxide: an effective treatment option for erosive pustular dermatosis of the leg. Br J Dermatol. 2020 Feb;182(2):495-497.

Also available in: Español (Spanish)