Most likely you don’t know the name of the sign, but if you work with older people, you’ve probably seen the lesions it describes on more than one occasion 😉 In fact, they are a frequent reason for consultation.

The “sitter sign” refers to the rough, thickened skin that older people often develop near the intergluteal cleft, associated with immobility and continued sitting. It is also known by other more complicated names, such as gluteal senile dermatosis or hyperkeratotic lichenified skin lesion of the gluteal region.1 The latter name, although more cumbersome, actually describes the disorder well:). Gluteal senile dermatosis was first described in Japan in 1979 and, since then, the few publications on this pathology are predominantly cases and case series from Asian countries.2,3 However, despite the lack of published studies in our setting, it is also very prevalent in Western countries.

What are the triggers?

The fundamental causes appear to be advanced age (thinning and loss of skin elasticity), prolonged sitting (with consequent pressure and friction) and a low body mass index.2,3 Affected individuals spend most of their time sitting. It would be interesting to study the prevalence of these injuries in young people who require continuous wheelchair use.

Although the first published case series show a striking predominance of the male sex, it is a pathology that is equally prevalent in women.2,3

How does it present clinically?

Typically, hyperkeratotic, scaly, ill-defined, brownish-red to grayish, poorly defined plaques slowly develop in the intergluteal cleft and on both buttocks. This characteristic distribution pattern of lesions is reminiscent of the “three vertices of a triangle”.2,3 In addition to darker, non-inflammatory plaques, inflammatory plaques with a psoriasiform appearance may be observed.

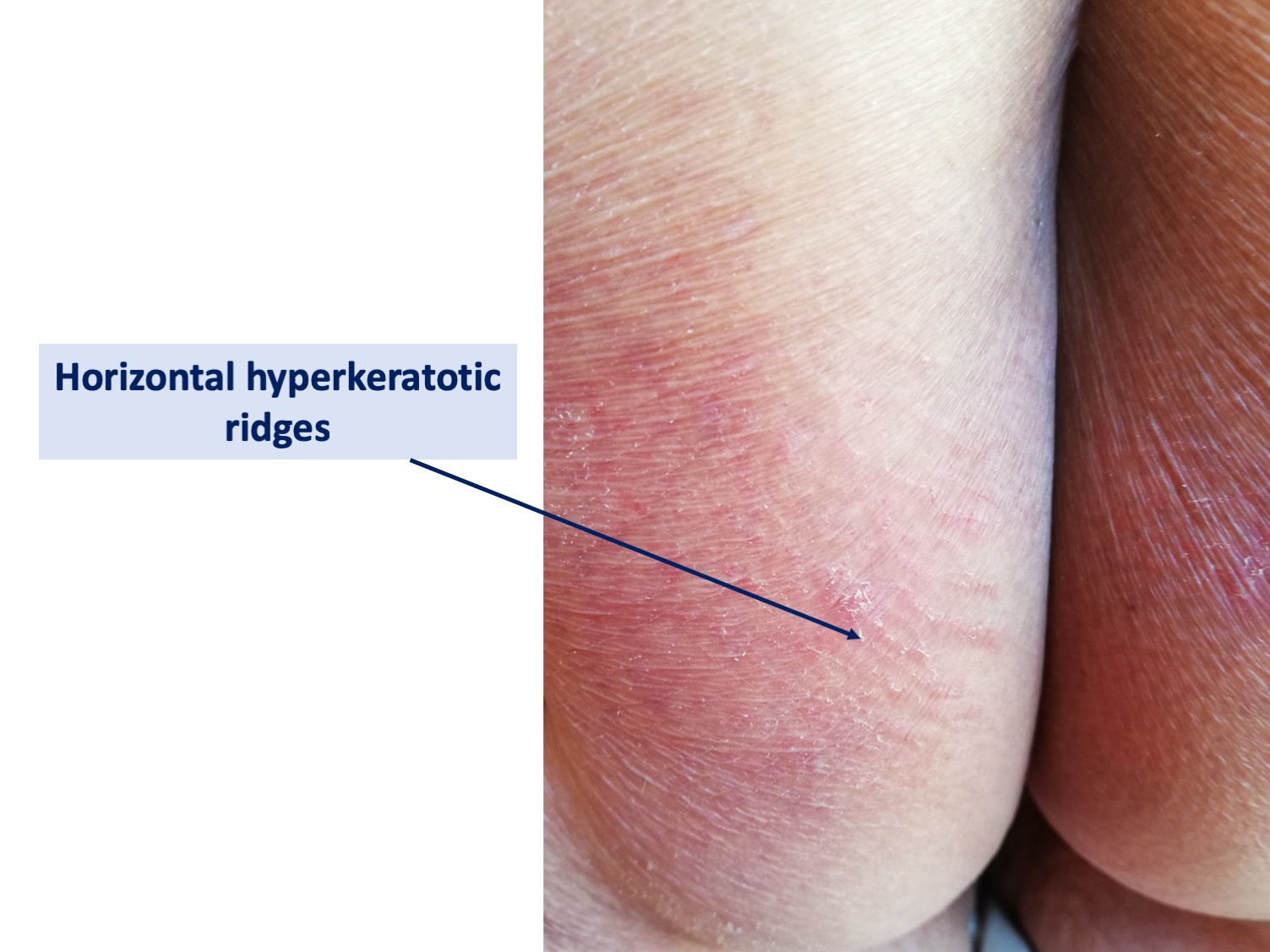

The most frequent, but not exclusive, location of plaques on the buttocks is in the area of the ischial tuberosities and lesions of the gluteal cleft do not necessarily coincide with the coccygeal apex. However, there are incomplete forms, as some patients have lesions only in the buttocks and not in the intergluteal cleft, or only in the intergluteal cleft, and sometimes only one buttock is affected. The appearance of hyperkeratotic ridges perpendicular to the buttocks has been described as typical.2,3

Erosions and ulcers of different depths may also appear.

They are usually asymptomatic lesions, but may cause discomfort when sitting, especially on unpadded surfaces. The discomfort includes itching, pain and foreign body sensation. Considering that in most cases they are asymptomatic and therefore do not cause consultation, it may be a much more prevalent pathology than is generally thought.

How is it diagnosed?

Diagnosis is clinical. We will only perform a biopsy to rule out other pathologies if we have doubts. In its differential diagnosis we will include irritative intertrigo, tinea, candidiasis, inverse psoriasis, eczema, lichen simplex chronicus and anosacral amyloidosis.2,4

If we biopsy, in most cases the histopathologic changes will be mild and characteristic, although not specific. Typical findings include orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia and vascular dilatation in the papillary dermis with little lymphohistiocytic infiltration. In more severe cases, additional changes appear: edema of the papillary dermis, dilatation and proliferation of small vessels down to the reticular dermis and a dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, as well as erosions or ulcers.4

These findings indicate a type of abnormal keratinization resulting from chronic friction. Thus, the wounds that appear in senile gluteal dermatosis occur from the epidermis that is thickened, which differentiates them from pressure injuries, in which epidermal damage is secondary to necrosis due to ischemia and cellular stretching.

How is it treated?

Senile gluteal dermatosis often responds poorly to topical corticosteroid treatment. Topical corticosteroid may relieve itching but does not usually improve hyperkeratotic skin lesions. On the other hand, keratolytic agents, such as salicylic acid or urea, also do not seem to give satisfactory results. The benefit of topical retinoic acid has been described, as it may help to control abnormal epithelial differentiation and desquamation. The use of emollients to prevent skin dryness is also recommended, in addition to frictionless washing and drying of the area. When wounds have already appeared, my experience with zinc oxide barrier products is good.

However, the most effective therapeutic measure is patient and family education on the importance of implementing lifestyle changes that include avoidance of prolonged periods of sitting. In addition, pressure relieving devices during sitting (in severe cases ideally static or dynamic air cushions) may be helpful.2,3

References:

- Dahl, M.V. (2014). Sitter’s Sign. NEJM Journal Watch, 2014.

- Moon SH, Kang BK, Jeong KH, Shin MK, Lee MH. Analysis of clinical features and lifestyle in Korean senile gluteal dermatosis patients. Int J Dermatol. 2016 May;55(5):553-7.

- Liu HN, Wang WJ, Chen CC, Lee DD, Chang YT. Senile gluteal dermatosis: a clinical study of 137 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2014 Jan;53(1):51-5.

- Liu HN, Wang WJ, Chen CC, Lee DD, Chang YT. Senile gluteal dermatosis – a clinicopathologic study of 12 cases and its distinction from anosacral amyloidosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012 Feb;26(2):258-60.

Also available in: Español (Spanish)