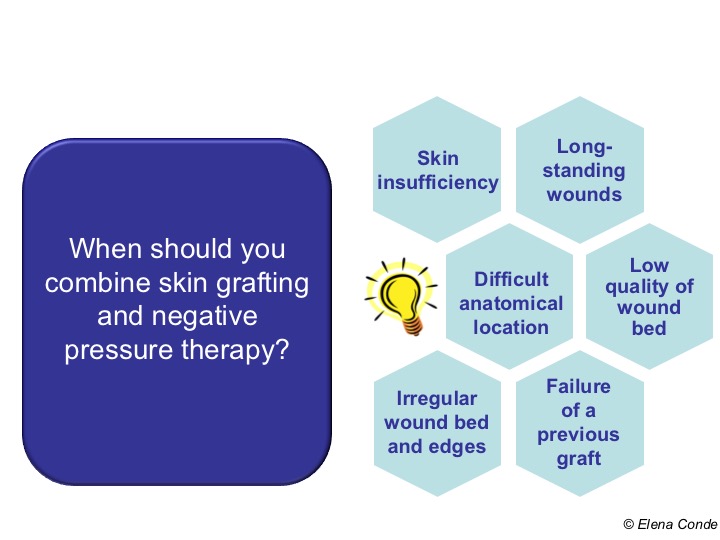

In previous posts we have talked about the benefits that these two treatments have, separately, promoting healing. However, their combined use plays a fundamental role. On the one hand, their sequential use is of great interest, as the application of negative pressure promotes the formation of granulation tissue, with reduction of exudate and bacterial load, and therefore prepares the wound bed to facilitate graft taking. On the other hand, its synchronous use can improve the percentage of graft taking,1-6 especially in certain situations that we will now point out.

As I commented in previous posts, among them “Types of skin grafts to cover chronic wounds: which one to choose“, in our wound clinic we normally use punch grafts. These partial thickness grafts are dermo-epidermal fragments more or less circular or oval, which are usually obtained with punch (punch), scalpel or curette, without deepening beyond the papillary dermis. The procedure is performed under local anaesthesia in the donor site, usually the thigh. The fragments are placed directly on the wound bed, without any type of fixation, apart from pressure and local immobilization during the first days after the procedure.

Most authors of the published studies about the benefits of negative pressure therapy in skin graft taking, use mesh skin grafting, which is another type of partial thickness graft.3-5 However, a clinical trial involving 60 patients with chronic leg ulcers treated with punch grafts finds a statistically significant reduction in healing time, pain and treatment costs in the group that received associated negative pressure therapy.6

The major determinant of the success of skin grafting is its attachment to the wound bed. It also represents the greatest challenge, especially in chronic wounds in particular anatomical locations (Achilles tendon, ankle), where graft attachment to the wound bed is difficult. On the other hand, we cannot forget that advanced age is a constant feature in patients with wounds and, therefore, so is skin fragility (dermatoporosis). The pressure that must be exerted on the grafts to favour graft taking (and the friction of the material used) can produce the opposite effect in patients with skin ageing, as it can damage capillaries and trigger bleeding and haematomas. In addition, although the ideal situation is to graft wounds with optimal granulation tissue, our experience tells us that this is not easy to achieve with chronic ulcers of long evolution in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. Conclusion: the majority of wounds that we graft do not present a perfect microenvironment for the reception of those skin fragments. Although grafts that do not take are also interesting because they release growth factors and other molecules and cells that promote healing, the more percentage of graft taking achieved, the better.

There are different negative pressure therapy devices commercially available on the market. We use a portable, single-use device with a pump that exerts a pressure of -80 mmHg on the dressing that we place on the wound covered with the grafts.

Our experience, like that of other professionals, confirms the benefit of applying negative pressure therapy on skin grafts. Its efficacy is associated, on the one hand, with a reduction in exudate and better immobilization and sealing of the grafts, with the consequent decrease in shear and, therefore, lower risk of development of seromas and hematomas.1-6 On the other hand, it has been proposed that the mechanical stretching that produces negative pressure can both stimulate the signaling pathways that promote keratinocyte mitosis and activate neo-angiogenesis by increasing microcirculatory flow in the wound bed and edges.2

I cannot finish a post that includes the word “successful” in the title without referring to the underlying engine of every successful idea and treatment strategy in our wound clinic: I AM PART OF A WONDERFUL TEAM.

References:

- Gupta S. Optimal use of negative pressure wound therapy for skin grafts. Int Wound J. 2012;9(Suppl 1):40–7.

- Azzopardi EA, Boyce DE, Dickson WA, Azzopardi E, Laing JH, Whitaker IS, Shokrollahi K. Application of topical negative pressure (vacuum-assisted closure) to split-thickness skin grafts: a structured evidence-based review. Ann Plast Surg. 2013 Jan;70(1):23-9.

- Moisidis E, Heath T, Boorer C, Ho K, Deva AK. A prospective, blinded, randomized, controlled clinical trial of topical negative pressure use in skin grafting. Plast Reconst Surg 2004;114:917–22.

- Llanos S, Danilla S, Barraza C, Armijo E, Pineros JL, Quintas M, et al. Effectiveness of negative pressure closure in the integration of split thickness skin grafts. A randomized, double-masked, controlled trial. Annals of Surgery 2006;244(5):700-5.

- Maruccia M, Onesti MG, Sorvillo V, et al. An Alternative Treatment Strategy for Complicated Chronic Wounds: Negative Pressure Therapy over Mesh Skin Graft. BioMed Research International. 2017;2017:8395219.

- Vuerstaek JD, Vainas T, Wuite J, Nelemans P, Neumann MH, Veraart JC. State-of-the-art treatment of chronic leg ulcers: A randomized controlled trial comparing vacuum-assisted closure (V.A.C.) with modern wound dressings. J Vasc Surg. 2006 Nov;44(5):1029-37

Also available in: Español (Spanish)