Sharp or surgical debridement of an ulcer involves the use of a scalpel blade to remove necrotic or sloughy tissue. Unlike other types of debridement, such as autolytic or enzymatic debridement, it has the advantage of speed in removing nonviable tissue, sometimes in a single session. But it also has its disadvantages, such as possible bleeding or pain, and certain contraindications.

The three best known contraindications are: severe peripheral artery disease until it has been revascularized, dry necrotic plaques on heels and active pyoderma gangrenosum. Let’s look at these last two in more detail….

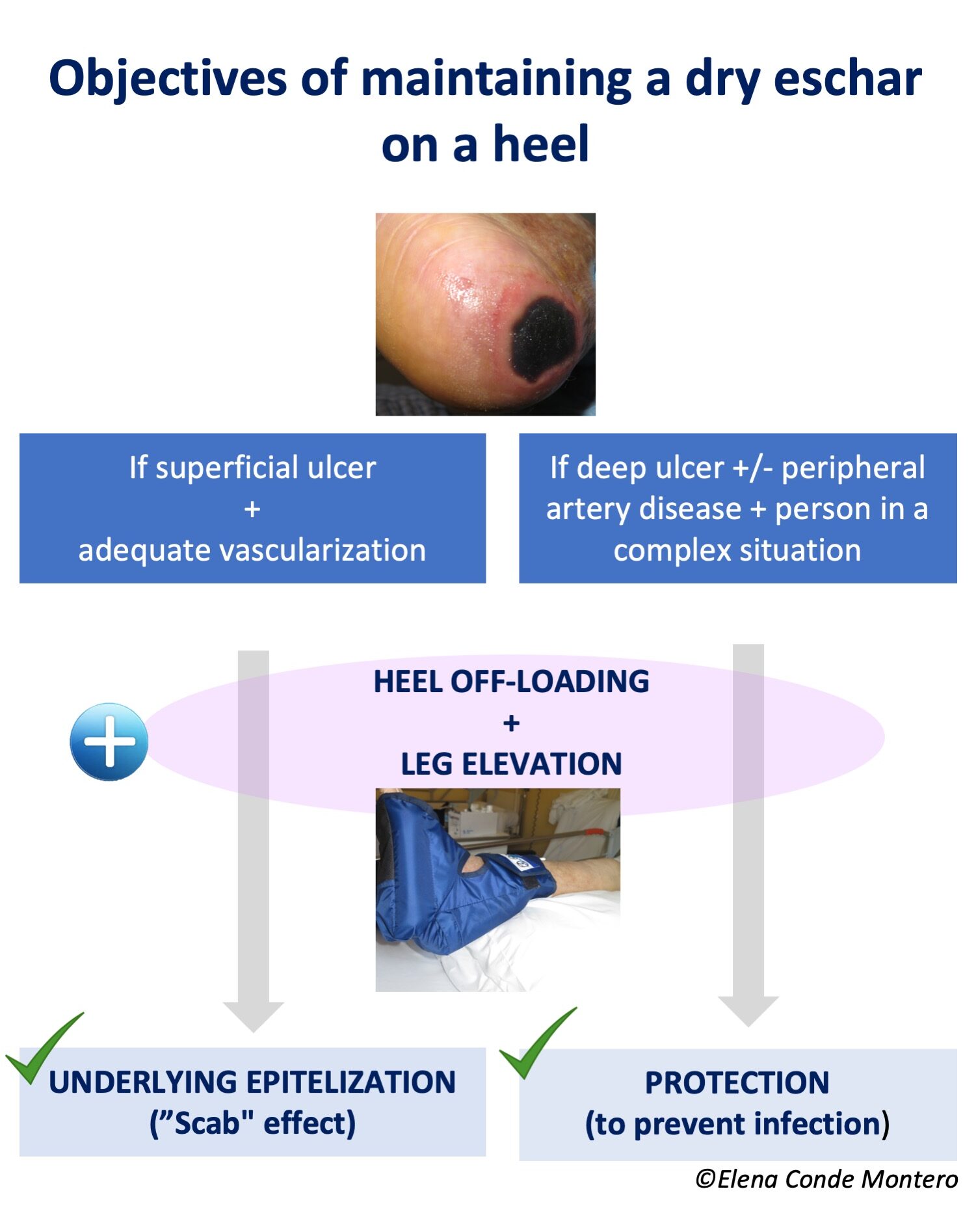

Why should we not remove dry necrotic plaques on the heels?

Because being dry, adherent to the bed, without fluctuation or other signs of infection, they have a protective function. Keeping that protective plaque dry can prevent bacterial proliferation and have a “scab effect”. In addition, it avoids the pain of sharp debridement and the possibility of leaving exposed deep tissues (calcaneus) with potential for infection.

If the ulcer is superficial, not very extensive and the vascularization is adequate, this scab could promote the underlying epithelialization. On the contrary, if the ulcer is deep and extensive, there is associated peripheral arterial disease and/or the patient’s complex situation does not allow another attitude that favors healing, the objective will be exclusively to maintain the “protective scab” to avoid superinfection (palliative protection or prior to revascularization or amputation). See post: “Do not debride dry schars on heels“.

What is the phenomenon of pyoderma gangrenosum patergia?

Pyoderma gangrenosum is characterized by uncontrolled activity of the immune system, predominantly neutrophils, with production of necrosis and skin ulcers. It may appear spontaneously or be triggered by minor trauma or surgery. This inflammatory hyperreactivity is called patergia phenomenon and can appear after sharp debridement (See post: “Pyoderma gangrenosum: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge“). In fact, debridement can rapidly increase the extent and depth of the ulcer. To avoid this, we will only perform this type of debridement when immunosuppressive treatment has adequately controlled the inflammatory activity and there are no signs of activity (See post: “How to promote healing in ulcers secondary to pyoderma gangrenosum?”).

The three contraindications we have just seen are the most agreed upon. However, there are other situations in which sharp debridement can worsen wound evolution, such as Martorell ulcer or ulcers secondary to vasculitis.

Why can a Martorell ulcer be worsened by sharp debridement?

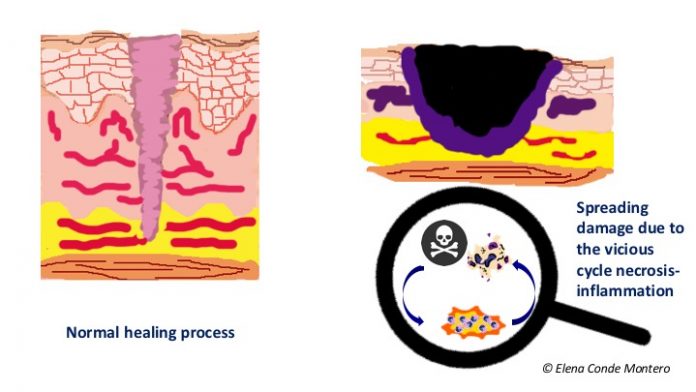

Extensive sharp debridement can behave like trauma, with a first phase in which vasoactive substances are released to produce vasoconstriction to limit tissue damage, bleeding and facilitate clot formation. To this end, the arterioles limit the flow by contracting. Following this vasoconstriction, there is significant vasodilatation with increased permeability of the arteriolar wall, so that cells (neutrophils, macrophages) and inflammatory molecules are provided to the wound bed.

Patients with Martorell ulcer present subcutaneous arteriolosclerosis, i.e., less reactivity of the arteriolar wall, calcifications and decrease in caliber, this vasoconstriction may imply a compromise of tissue irrigation prolonged in time, with consequent ischemia. Subsequent vasodilatation with release of inflammatory mediators increases necrosis (cell death), and here the vicious circle of necrosis-inflammation begins. Necrosis secondary to this inflammation would maintain the pro-inflammatory mediators with consequent extension of the wound.

This occurs not only in Martorell ulcer, but in the whole spectrum of arteriolosclerosis ulcers (See post: “Little is said about arteriolosclerosis ulcers“).

BEWARE! This possible worsening with sharp debridement, in addition to the frequent finding of an abundant inflammatory infiltrate in superficial biopsies, may lead to misdiagnosing of Martorell ulcer with pyoderma gangrenosum.

Taking this into account, although sharp or surgical debridement is considered the first choice prior to graft coverage, in our practice we try to be as conservative as possible, with minimally invasive debridement and early and sequential punch grafting (see post: “Interest of early punch grafting in Martorell hypertensive ischemic ulcer“).

What about vasculitis?

It is not uncommon to see increased necrosis after sharp debridement in the acute phase of vasculitis in which, in addition to inflammation, there is vascular occlusion. This worsening could be framed within the concept of “vicious circle necrosis-inflammation” that we have just explained. Therefore, as in pyoderma gangrenosum, in ulcers due to vasculitis it is recommended to wait until immunological activity is adequately controlled by immunosuppressive treatment. As in the case of pyoderma gangrenosum, the control data of the inflammatory activity are not always easy to identify…

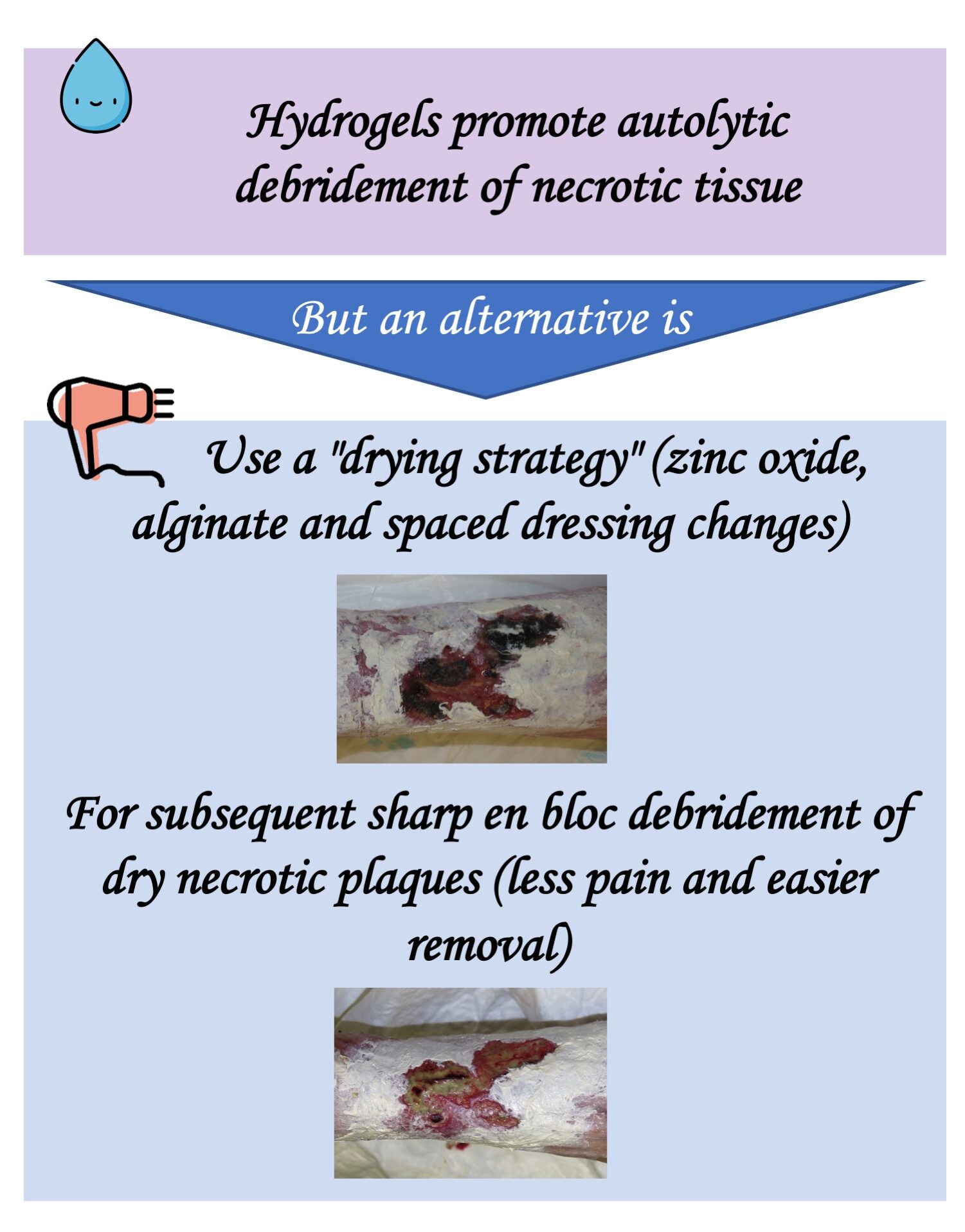

I would like to end with a therapeutic pearl that can facilitate sharp debridement of necrotic plaques. It is a drying strategy to make the subsequent removal of the plaques with the scalpel less traumatic and painful 😉

The idea to write this post came to me in a session on atypical wounds at the World Union of Wound Healing Societies Congress just held in Abu Dhabi:) I am happy to be back at congresses. There are many ways to share knowledge, but in person will always be more enriching. Life is about meeting people;)

Also available in: Español (Spanish)